Immunotherapy could be improved by understanding T-cells with stem cell-like characteristics

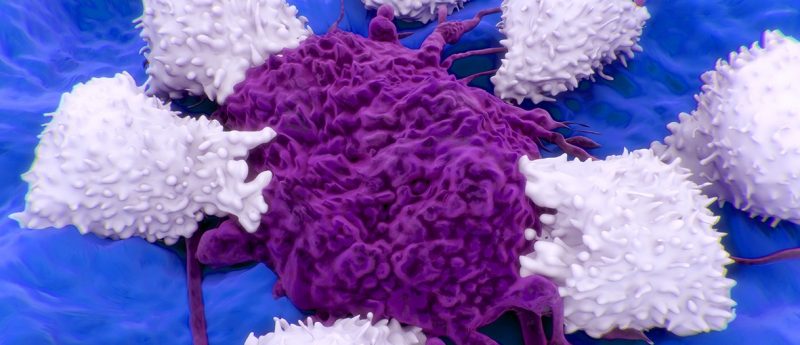

T-cells with stem cell-like qualities, found within tumors and their microenvironments, could help to improve patient response to immunotherapy.

Researchers at the University of Lausanne (Switzerland), have recently published an article in Science Translation Medicine proposing that a novel population of T-cells could alter our understanding of the microenvironment and our approaches to immunotherapy. Werner Held (University of Lausanne) has stated that a distinct population of T-cells possess stem cell qualities, which may allow researchers to improve the efficiency of one of the most common immunotherapies.

Recently, transcriptionally distinct populations of CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells have been identified, which demonstrate self-renewal and differentiation potential reminiscent of stem cells. These cells express a PD-1+ TCF1+ phenotype and appear to act as a reservoir for the more differentiated CD8+ TCF1- cells, which comprise the bulk of the tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. The different surface markers have allowed these cells to be separated and analyzed and it is the hoped that they may be fully exploited to improve immunotherapy.

Immunotherapy has not met initial expectations in many cases, with clinical trials failing to demonstrate the desired improvements; however, the use of “checkpoint inhibitor” drugs that target the PD-1 protein have been the success story of the field. Despite this, the response to these drugs is still lower than is desirable and researchers endeavor to increase their effectiveness.

Immunotherapy against PD-L1+ tumors utilizes the T-cells’ normal functions as they patrol a patient’s body searching for foreign objects to remove. These T-cells would normally target the tumor cells; however, tumor cells have developed strategies to avoid detection. By expressing the PD-1 ligand, PD-L1, tumor cells can escape detection and survive. Treatment with checkpoint inhibitors disrupt this PD-1:PD-L1 interaction, exposing the tumor cells to cytotoxic CD8+ T-cells. This eventually leads to tumor death or the suppression of growth.

Despite being recently identified, there is already evidence that this new PD-1+ TCF1+ population may have a direct impact on the effectiveness of immunotherapy. The ratio of these stem cell-like cells to their differentiated progeny seems to inversely correlate with progression free-survival after treatment with checkpoint inhibitors, suggesting they may be utilized to improve the effectiveness of the therapy.

Source: Held W, Siddiqui I, Schaeuble K, Speiser DE, Intratumoral CD8+ T cells with stem cell—like properties: Implications for cancer immunotherapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 11 eaay6863 (2019)

FAQ

How does immunotherapy work?

Immunotherapy is the concept of using a patient’s own immune system to combat cancer. There are various ways that the therapies aim to achieve this, including highlighting cancers with markers that the immune cells can detect and destroy; using antibodies to block vital cell surface receptors; or recently, the innovation of CAR-T therapy which removes a patient’s functioning T-cells for them to be genetically altered, prior to being transplanted back into the patient. All these therapies aim to enhance, train or utilize the immune system to work towards eliminating the patient’s cancerous cells.

Why use immunotherapy instead of chemotherapy?

Immunotherapy is designed to embrace the natural mechanisms within the patient’s body to eradicate the cancer cells. This is a beneficial approach compared with conventional therapies, which are primarily designed to cause severe damage to any quickly growing tumor cell, because chemotherapy indiscriminately damages all dividing cells, whether cancerous or not. Chemotherapy also ignores those cancerous cells which are not dividing quickly, allowing these cells to act as a reservoir and reestablish the cancer. The hope is an immune system trained against cancer cells would find these remaining cells and reduce the risk of relapse. However, while immunotherapy sounds excellent in principle, results currently vary wildly between approaches, patients and cancer types.

Have any additional questions about this story? Ask us in the comments, below.