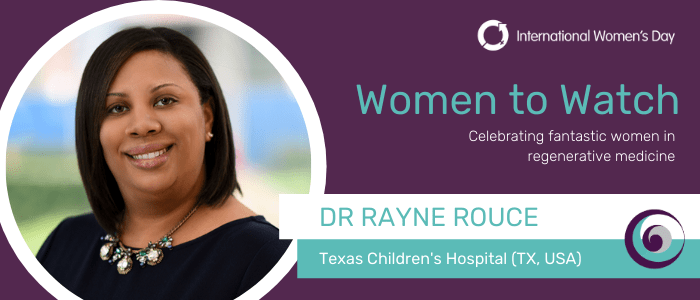

Women to Watch: translating CAR-T therapies from the lab to the clinic with Dr Rayne Rouce

As part of our ‘Women to Watch’ series on RegMedNet, we’re putting Dr Rayne Rouce into the spotlight. Dr Rouce is a pediatric oncologist and physician–scientist at Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital (both TX, USA) focused on translating novel immunotherapies from the laboratory to the clinic. Specifically, she leads clinical trials of first-in-human genetically or otherwise modified T cells (CAR and virus-specific T cells) in patients with relapsed or refractory leukemia and lymphoma. In addition to translating novel therapies, she has worked in the laboratory and has partnered with other scientists to assist in the translation of these exciting therapies into the clinic.

Can you provide us with an overview of what your work involves?

My work is extremely satisfying, as I am truly involved in every aspect of bench-to-bedside development of these immune effector products: from preclinical conception and testing of these T-cell products, to optimization and validation in preparation for investigational new drug application submission, to protocol development and regulatory submission, to enrollment and day-to-day care of patients receiving these groundbreaking therapies.

What are the best aspects of your job? What are the most challenging parts?

The best part of my job is that I literally get to be a part of giving patients, particularly children suffering from these horrible cancers, a chance at life. The clinical trials that I lead are Phase I, thus typically reserved for patients who may have been told they have no further treatment options. I cannot express the gratitude I feel to each and every patient and family who has ever enrolled on a clinical trial I’ve led. It is an honor to walk with them through such a difficult time of their journey. Regardless of outcome, my colleagues and I, and the field of cellular and gene therapy, are forever grateful for the many sacrifices these patients and their families make, and their willingness to help us learn how to improve our therapies. Also, it should be obvious from the description of my work, that it is the epitome of ‘team science’. On a daily basis, I get to work with and learn from countless scientists, lab personnel, regulatory professionals and healthcare professionals with various expertise. We work as a finely oiled machine with many moving parts, and only the occasional snag, which we work to troubleshoot together.

I would say the most challenging aspect is coming to grips with the current limitations of science and medicine, and how they affect my patients. I don’t think in terms of scientific protocols or therapeutic products – I think in terms of patients. Little faces, big smiles, big dreams. When I can’t offer a certain therapy because it has not been tested yet in children, or despite its promise, it remains in preclinical development… I feel defeated. However, it is this very sense of defeat that gives me the fiery resolve to not stop until I have a promising therapy to offer to every patient I encounter.

Have you faced any obstacles in your field due to your gender?

As a Black woman physician–scientist, I certainly have faced a number of obstacles. However, I have never encountered a barrier that was not surmountable, and I can honestly say that every challenge I’ve endured has added to my toolkit of negotiation and conflict resolution skills, and my general ‘academic awareness’. In my field, I am usually the only person of color in the room, often the only one with a Southern drawl, and occasionally one of few women. Nevertheless, I have had amazing women mentors who have paved the way and shown me when to be gracious, and when to speak up.

In your opinion, what more could be done to promote gender equality in your field?

Women are promoted less often than men and are less likely to gain academic tenure. They are paid less, are less likely to be in leadership positions, and more likely to engage in work that, while meritorious at face value, is less likely to contribute to promotion. And yet, historically, we often don’t ask for what we have earned. So, what can we do? Know our worth. Speak up. Ensure others understand that one token woman at the table is not enough. Then once we arrive, once we’ve made it, ensure we pay it forward, smoothly paving the pathway for women behind us.

What advice would you give to young women hoping to pursue a career in your field?

The sky is the limit. Never be intimidated. Replace that ‘imposter syndrome’ with ‘superwoman syndrome’. Recognize that while you may be the first, you won’t be the last. Identify leaders you strive to emulate and don’t be shy about asking them to mentor you. Lastly, when people believe in you – believe them, and let that fuel your self-confidence.

Lastly, who is your female superhero?

Wow. Now THIS, is a hard one. I would say my female superhero is a combination of Michelle Obama, Rosa Parks, Katherine Johnson, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Beyoncé and my mom and grandmother. While these women may seem like they have nothing in common – in my mind, they have everything in common. They broke down barriers and paved the way, all the while keeping their heads held high.

Acknowledgements

This interview was put together and conducted by our Senior Editor, Sharon Salt, with written responses provided to us by Dr Rayne Rouce.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this interview are those of the interviewee and do not necessarily reflect the views of RegMedNet or Future Science Group.

You might also like:

- Women to Watch: exploring the therapeutic potential of stem cells with Dr Vivian Li

- Women to Watch: cryopreserving ovarian tissue with Maxine Semple

- Women to Watch: moving cell therapy products towards validation with Stacey Brower

- Women to Watch: developing precision medicine therapies for brain tumor patients with Dr Analiz Rodriguez